Whale Evolution

Whale evolution is one of the most fascinating examples of evolution that there is.

Whales, like all mammals, evolved from reptiles, amphibians, and fish. Thus, over hundreds of millions they left the sea, grew legs, grew fur, and evolved lungs. Then they returned to the sea, lost their legs and fur, but kept their lungs.

Unbelievable, but one of the most well-attested line of fossils there is.

More amazingly, Dr. Hans Thewissen, perhaps the leading specialist in whale evolution, tells us the transition from a completely land animal to a completely marine animal took only 8 million years.

On top of this, the end of whale evolution—the cetaceans, the order to which whales belong—are often more adept at life in the sea than fish! (Otters can outswim many fish, too!)

In the Beginning … No, Let's Skip the Beginning

Cetaceans are mammals, the only mammals that live (all the time) in the water. The evolution of mammals will be covered elsewhere, so let's skip that whole portion of the evolution of whales.

There are areas, from over 50 million years ago, where scientists are disagreed (and very excited about continuing to learn more) over which order whales evolved from. However, once we hit the pakicetids, 53 million years ago, the evidence starts nailing down the series for us.

Since we are excited to be able to go back 6 to 7 million years with man, the 53-million-year story of whale evolution is remarkably complete!

The Pakicetids

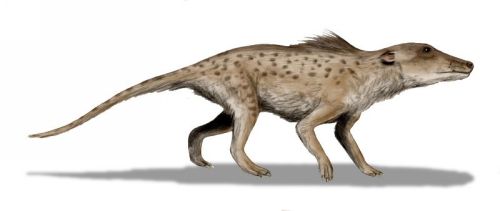

Pakicetus

PakicetusPhoto by Arthur Weasley

Used with permission

The pakicetids are a family of mammals that looked something like dogs with hooves. The feature that pakicetus shares in common with modern whales is their ears. Cetaceans have an ear structure that is unique to their order. Pakicetids share that structure with them.

There is some resemblance in the teeth as well.

Pakicetids are land animals, and they begin the series of fossils that are believed to be the direct ancestors of whales.

Ambulocetids

"If you had given me a blank piece of paper and a blank check, I could not have drawn you a theoretical intermediate any better or more convincing than Ambulocetus. Those dogmatists who by verbal trickery can make white black, and black white, will never be convinced of anything, but Ambulocetus is the very animal that they proclaimed impossible in theory."

– Stephen Jay Gould

Natural History Magazine, May 1994

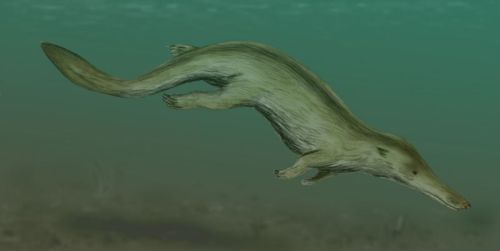

Ambulocetus was like hitting the mother lode in whale evolution. It was the perfect intermediate, the ultimate missing link between land mammals and sea mammals.

The ambulocetids have the cetacean ear structure. They have hind legs, but they are better adapted for swimming than for walking. They have an adaptation to their nostril that allows them to swallow underwater, and their ears are not external. They likely had to set their head on the ground to feel for vibrations in order to hear on land.

Chemical analysis of their teeth has shown them to be adapted to both fresh and sea water. It's thought that they would lurk near the water's edge and snatch victims when they came to drink. It was about 9 feet long, and it lived 50 to 49 million years ago.

The path to the water had started, and very clearly at that.

Kutchicetids

Kutchicetus minimus

Kutchicetus minimusPhoto by Arthur Weasley

Used with permission

Kutchicetus is a genus of the order Remingtonocetidae, which lived about 46 million years ago. It was only about the size of a sea otter.

Here in the remingtonocetids we have the first development of mechanisms for transmitting sounds under water, which may have been used for some sort of communication, but, more importantly, lays the foundation for the later echolocation (sonar) systems known to be in dolphins and many modern whales.

Small and just one genus of the Remingtonocetids, kutchicetus is nevertheless a crucial step on the way to full marine status in the evolution of whales.

Rodhocetids

Rodhocetus, a rather fearsome-looking creature

Rodhocetus, a rather fearsome-looking creaturePhoto by Pavel Riha | Used with permission

Rodhocetus belongs to the family of protocetids. It was the first aquatic whale, dating from 47 million years ago. It had large rear feet to paddle through the water with.

Rodhocetids have only been discovered since 2001. Their ankles give some indication that the whale lineage actually goes back through artiodactyls (the ancestors of hippos and pigs). Rodhocetids have a "double-spooled" trochlea on its tibia, a feature unique to the artiodactyls.

Significant modifications are that the sacral vertebrae (our tailbone) are unfused, unlike its predecessors, which increase power and flexibility. Its pelvis is still shares a joint with the sacrum, allowing it to bear weight on land, if it ever went on land. The hind limbs are shortened, and the nostrils have begun to creep up the skull.

Rodhocetus and the protocetids represent a major advance in whale evolution.

Rodhocetus' ankle bones

Rodhocetus' ankle bonesas found by Philip Gingerich

Used with permission

Basilosaurus

Basilosaurus isis skull at the Senckenberg Museum

Basilosaurus isis skull at the Senckenberg Museum"Basilosaurus isis 3" by Ghedoghedo - Own work | Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Commons.

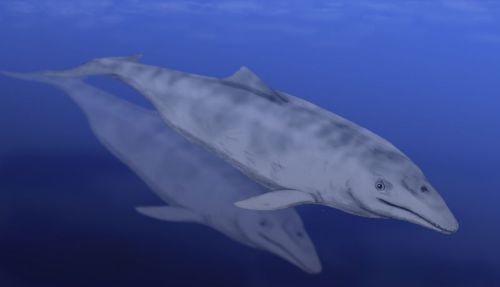

Basilosaurus was originally found in 1840 and got its name because it was mistaken for a reptile.

Basilosaurus starts to resemble modern whales. It's quite large, up to 60 ft. long, and its pelvis is no longer attached to the vertebral column. All ability to support itself on its hind legs, which it still had, is gone.

It lived 40 to 34 million years ago. So many fossils of its family have been found in the Valley of the Whales in Egypt that there are several known species of Basilosaurs, some smaller than the original found in 1840.

Whale evolution had accomplished complete marine status while not yet losing all the baggage from life on land.

One interesting side note: a person claiming to be a scientist wrote me with a long argument that Basilosaurus was actually a reptile. I wrote back and asked, "Don't Basilosauruses wave their tails up and down like whales, not left to right like fish and reptiles?" He quit writing to me. One of the evidences that air-breathing submarine animals like whales and dolphins descended from land mammals is that their tails move vertically, not horizontally like fish and reptiles.

Dorudon

Dorudon

DorudonPhoto by Arthur Weasley

Used with permission

Dorudon is actually a member of the Basilosaur family, but it's smaller—more like 16 ft. long—and shaped more like a dolphin. Its nostrils have made it halfway up the snout. On modern whales and dolphins, of course, it's on top of the head.

Squalodon

Squalodon is the first whale that appears to have the equipment to echolocate. It lived 34 to 18 million years ago, along with several other known species of whales.

Squalodon maintained the complex teeth of its ancestors. Land mammals tend to have several different kinds of teeth, but whales usually have only one. Other contemporaneous whales were evolving the simply conical teeth of modern whales, but Squalodon still had the ancient ones.

As part of the whale evolution series, squalodon probably went extinct. So let's turn to the lineages that are still around today.

Aetiocetids

Aetiocetus

AetiocetusPhoto by Arthur Weasley

Used with permission

Aetiocetus is considered the link between toothed whales and the mysticetes or balleen (toothless) whales. It lived about 25 million years ago.

Aetiocetus had both balleen and a full set of teeth. This strange combination is made even stranger by the fact that its teeth were mixed, like its ancestors. The toothed whales, who were evolving at the same time, were developing teeth of all one kind.

Aetiocetus also had a loose jaw, reminiscent of the modern mysticetes.

With the aetiocids we complete our whale evolution series. Since 30 million years ago, when aetiocetus existed, there are many, many more fossils and species, but the series here presented is ample—even beautiful—evidence of the evolution of whales. Rather than make this page longer and tedious, we will stop with these most important whale fossils and families.

Summation of Whale Evolution

What a terrific series of fossils!

This series of fossils takes us from a hoofed land animal to a marine animal with back legs that cannot support it in just a few million years. The spine has changed, the limbs have shortened, the nostrils have moved, the skull has changed in shape, and the brain has changed in its function.

Along the way, all these species are linked by a special set of ear bones unique to this lineage. The timing of the fossils is right, and the progression is evident. It would be hard to imagine asking for better evidence of whale evolution.

This series of fossils is a powerful argument for evolution, but of course there are people who cannot accept that because of their religion. I address their arguments here.

But I need to add a quote I found concerning the vestigial hind limbs that are found in all Right whales:

Nothing can be imagined more useless to the animal than rudiments of hind legs entirely buried beneath the skin of a whale, so that one is inclined to suspect that these structures must admit of some other interpretation. Yet, approaching the inquiry with the most skeptical determination, one cannot help being convinced, as the dissection goes on, that these rudiments [in the Right Whale] really are femur and tibia. The synovial capsule representing the knee-joint was too evident to be overlooked. An acetabular cartilage, synovial cavity, and head of femur, together represent the hip-joint. Attached to this femur is an apparatus of constant and strong ligaments, permitting and restraining movements in certain directions; and muscles are present, some passing to the femur from distant parts, some proceeding immediately from the pelvic bone to the femur, by which movements of the thigh-bone are performed; and these ligaments and muscles present abundant instances of exact and interesting adaptation. But the movements of the femur are extremely limited, and in two of these whales the hip-joint as firmly anchylosed, in one of them on one side, in the other on both sides, without trace of disease, showing that these movements may be dispensed with. The function point of view fails to account for the presence of a femur in addition to processes from the pelvic bone. Altogether, these hind legs in this whale present for contemplation a most interesting instance of those significant parts in an animal—rudimentary structures. (John Struthers, d. 1899)

Here is the reference for the above quote found at biologos.org: [Struthers, John, M.D., Professor of Anatomy in the University of Aberdeen. (1881) "On the Bones, Articulations, and Muscles of The Rudimentary Hind-Limb of the Greenland Right-Whale (Balaena mysticetus)."]

This quote speaks for itself and still stands despite being more than 130 years old.

Return to Examples of Evolution